The Treachery of Looking

How a Single Sentence Traps Us in a Paradox—From Brautigan to Magritte, Cage, and Escher

Somewhere in a quiet room, someone is staring at a poem, convinced that something is wrong. The words sit obediently on the page, still and innocent, yet the mind wobbles, unsure of itself.

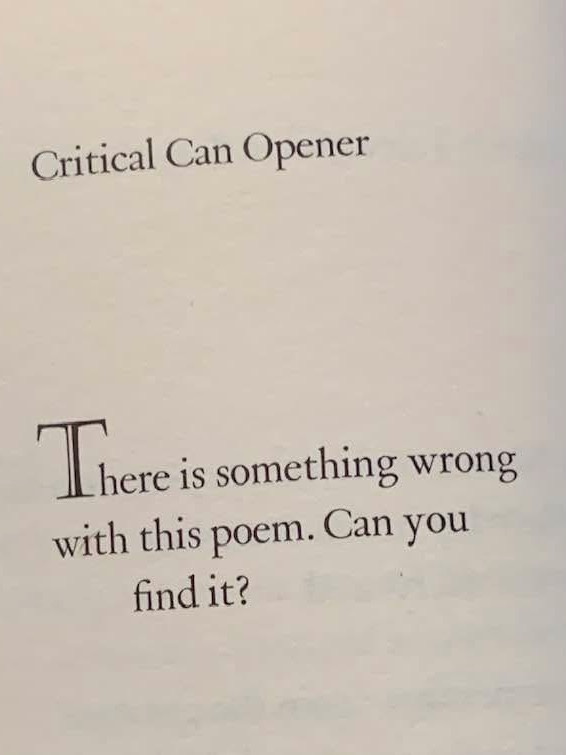

There is something wrong with this poem. Can you find it?

The challenge is simple, but the weight of it presses in, demanding attention.

If you tell someone there’s a problem, they will begin to search for one. This is the psychology of expectation—look closer, the mind whispers, see more than is there. And so, we become detectives of absence, scouring letters and syntax for cracks in meaning. Maybe the mistake is hidden in the typography, maybe in the way the words arrange themselves, or maybe in the simple fact that we are looking at all.

Richard Brautigan’s Critical Can Opener is not a poem in the traditional sense. It is a puzzle, a trick, a knot of words designed to unravel the mind. It does not need to be broken to be successful. Like Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, it reminds us that what we see is not necessarily what is there.

Magritte painted a pipe and wrote beneath it:

Ceci n’est pas une pipe—This is not a pipe.

A contradiction, but only if you refuse to step outside yourself. It is not a pipe, only the image of one. The moment you understand that, the paradox dissolves.

But our minds do not like dissolution. We crave structure, reason, the comfort of knowing that things are what they claim to be. The poem says something is wrong, and so we must believe it. The painting shows a pipe, and so we want it to be one.

We are like the audience in John Cage’s 4’33”, sitting in silence, waiting for the music to begin, only to realize that the silence itself is the performance. We are like Escher’s figures, walking up staircases that fold into themselves, trapped in an architecture of our own perception.

If there is an error in Critical Can Opener, it is the one we bring to it—the assumption that meaning is something solid, something fixed. But meaning is fluid, a trick of the light, a mirage in the desert. The treachery is not in the poem or the painting or the silent stage.

The treachery is in our belief that what we see should be what we expect.

So we keep looking, convinced there is something to find.

Image: Brautigan, Richard. Ommel Drives On Deep Into Egypt. 1970.