The Farmer and the Phantom

The Man Who Fell in Love with an Alien

There are stories so strange they feel like they were never meant to be spoken aloud, as if the act of telling them dissolves the membrane between the possible and the impossible. In 1978, Juan Pérez, a young boy from Argentina, claimed he met beings not of this Earth. He was not the first man to encounter the ineffable, nor would he be the last.

Pérez, then 12 years old, rode his horse into the mist near his family’s farm in Venado Tuerto, Santa Fe. The morning was thick with silence, the kind that settles before something extraordinary happens. A craft descended before him—silver, seamless, shaped like an idea rather than a machine. Its door opened, and inside was a figure both alien and familiar.

He stepped inside.

And what happened next?

The details blur, as they always do with encounters of this kind. The room around him seemed weightless, without walls. He was given food—something tasteless but nourishing. The being watched him, studying him as if he were the mystery. They spoke, though not with words. A flood of understanding passed between them, something Pérez later struggled to articulate, as if trying to translate light into language.

More than anything, he felt an overwhelming sense of connection—not attraction, not infatuation, but something deeper. The kind of connection Rainer Maria Rilke describes when he says, “For one human being to love another: that is perhaps the most difficult of all our tasks… the work for which all other work is but preparation.”

And then, just as suddenly, he was back.

The Shape of Longing

All myths begin with loss. Or rather, all myths are attempts to translate loss into meaning. Like Orpheus grasping at Eurydice’s disappearing form, Juan Pérez spent years longing for something he could neither name nor prove.

He told his family, the villagers. They laughed. He became a curiosity, then a ghost in his own town. His encounter should have made him special, but instead, it made him solitary. He was a farmer, after all. What use did he have for things that could not be touched, traded, planted?

He grew older, but the memory did not fade. It deepened. Became something else. He would return to the field at night, standing where the craft had landed, whispering questions into the sky.

Many who claim alien contact speak of an aching aftershock, as if proximity to the Other erases any ability to be content with the ordinary. The poet Li Bai, who drowned reaching for the moon’s reflection in the river, would understand. Some loves are impossible, and yet they leave a mark, a wound that does not heal because healing would mean forgetting.

The Ecology of the Impossible

We pretend we know what is real. But reality is slippery, porous. “We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning,” Jean Baudrillard wrote. Perhaps Pérez understood this before the rest of us did.

The woman in the silver ship did not fit into any category—she was not angel, nor demon, nor hallucination. She existed in the liminal space between fact and dream, the way all the best things do.

There is an old story about a man who dreams he is a butterfly, and when he wakes, he is no longer certain if he is a man who dreamed of being a butterfly or a butterfly now dreaming of being a man. In 1978, Juan Pérez met a woman who did not belong to this Earth, and the moment he touched her, he was no longer a man who lived on Earth either.

Was she real? Does it matter?

Reality is a net we cast to keep ourselves from drowning in the sea of the unknown. But sometimes, if we are very lucky, something tears through it, something that leaves us gasping, awake in the night, longing for what cannot be named.

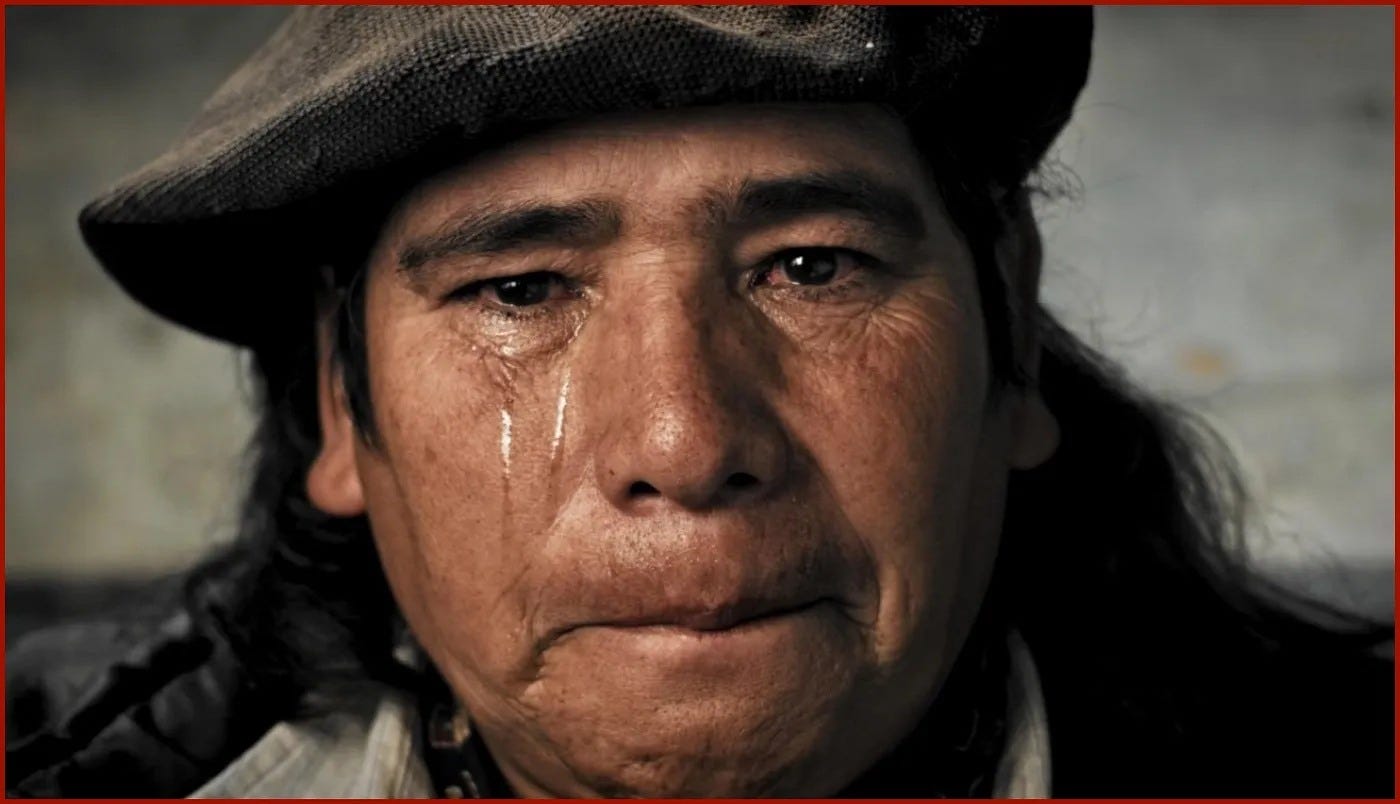

IMAGE: Witness of Another World. Directed by Alan Stivelman, performances by Juan Pérez, 1091 Media, 2018. Still image.