Orange World and the Wizard: Roadside Fantasies in Disney’s Shadow

On Highway 192, fiberglass fruit and a giant wizard stand beside motels where families live in the shadow of the Magic Kingdom.

Orange World Kissimmee History

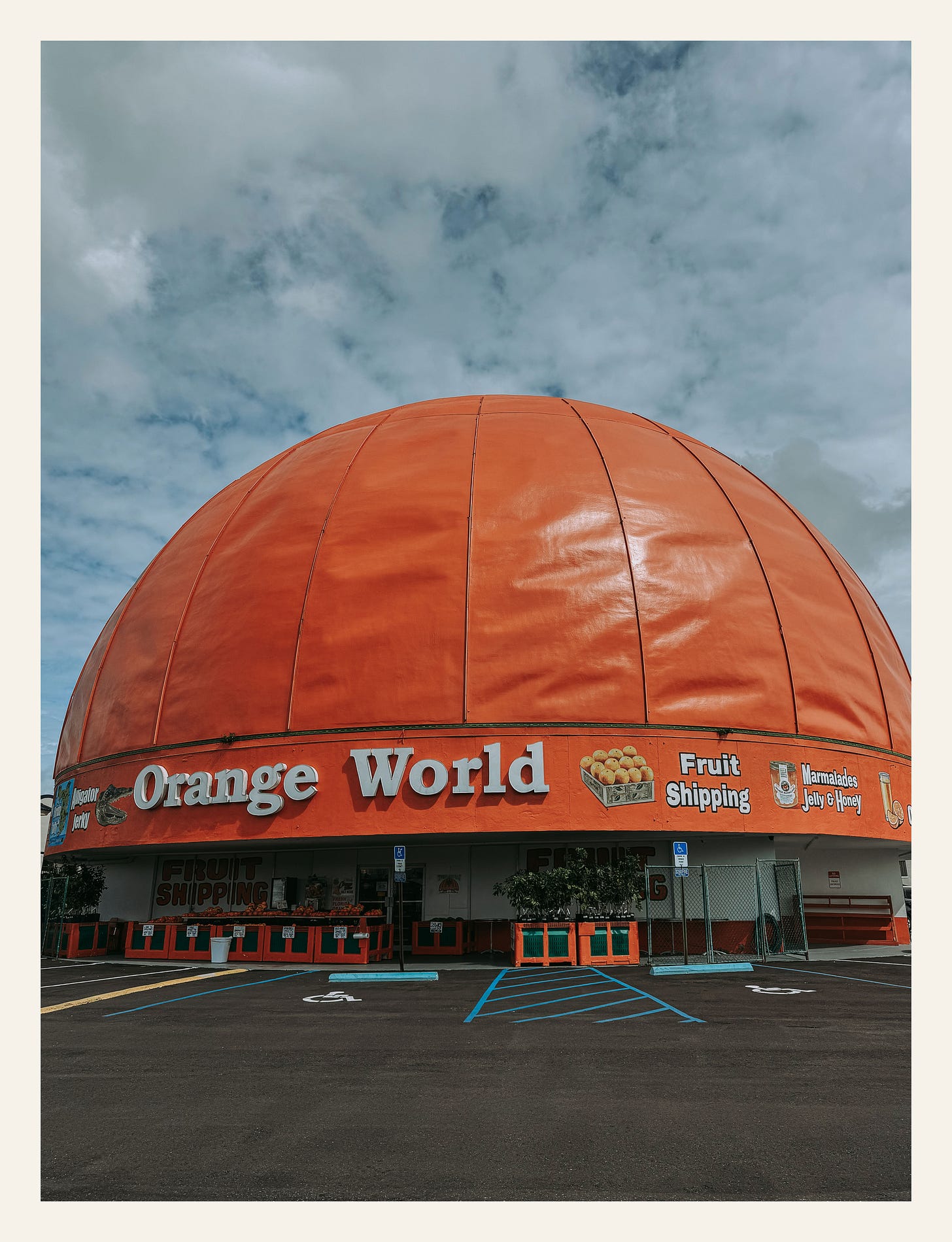

Highway 192 has plenty of neon and noise, but Orange World is the thing that catches your eye the most. A sixty-foot fruit sits in a parking lot like someone dropped it from the sky. The rind is painted bright, the leaf and stem tilted just enough to look cartoonish. The sign calls it the “World’s Largest Orange,” which is true in the same way a roadside dinosaur is the “World’s Largest.” It doesn’t matter if it is or isn’t. The size sells the story.

The building dates back to 1971, the year Disney World opened. At first it was just another souvenir shop, round and plain. Business slowed. The owner sat at the Waffle House next door and stared out the window at his lifeless store. He realized no one could tell what it was supposed to be. So he sketched on a napkin. By the early eighties the dome had been built, a fiberglass fruit bolted onto the roof. Locals say business tripled. That makes sense. A beige storefront is easy to ignore. A sixty-foot orange on the roadside will pull a car off the highway.

Orange World fits into a larger lineage of mimetic architecture, buildings shaped like the products they sell. Donuts in Los Angeles. A teapot in West Virginia. Florida went heavy on fruit. These places made the building itself the billboard, a trick of survival in an economy where attention is money.

It is also a parody of what used to exist here. Central Florida was once thick with citrus groves, thousands of acres of orange trees stretching across the horizon. Freezes, blight, and real estate speculation ate them away. Now the orange is fiberglass, hollow inside, standing in a parking lot surrounded by asphalt and chain restaurants. The real fruit is long gone.

Inside, the place smells like sugar and wax. There are citrus candies, plastic gators, t-shirts with palms, and flamingos. Tourists still pull in, not for what is sold, but to take a picture of themselves against the rind. The building itself is the prize.

Twistee Treat and Roadside Whimsy

Orange World is only one player in the roadside carnival that is Highway 192. A mile down, the roof of a building coils into a swirl of vanilla soft-serve, complete with cherry topper. This is Twistee Treat, another relic of mimetic architecture.

Twistee Treat is part of a chain, but here it feels at home beside the orange dome. Both are part of the same logic: turn food into buildings. Make it big enough to be unmistakable from a moving car.

Florida embraced this logic with a special intensity. Long before Disney, the state sold itself as spectacle. Alligator wrestling, mermaid shows, glass-bottom boats. The roadside had to match the mythology. Oversized fruit, sharks’ jaws, volcano mini golf courses. The orange dome and ice cream cone are not anomalies. They are extensions of a Florida tradition that runs on kitsch.

The roadside becomes a competition for imagination. Disney perfected fantasy at an industrial scale. The local shops had to out-weird it. If they couldn’t build castles, they could build giant food. And then, when the new millennium rolled in, they built a wizard.

The Wizard Gift Shop Orlando

There are few sights stranger than the Wizard Gift Shop rising over Highway 192 at dusk. A massive bearded figure looms across the facade, arms spread wide, staff glowing with neon. The wizard stretches the full width of the building, a fiberglass sorcerer presiding over a parking lot. I stood inches from the highway with a 50mm lens and couldn’t capture the entire facade.

Built around 2000, the shop is part of a wave of novelty facades that tried to keep pace with Disney’s dominance. There was a mermaid shop, a volcano facade, even a shark with an open jaw you could walk through. But the wizard was the boldest.

At night the staff glows like a signal flare. The parking lot fills with shadows, the wizard lit from below like a stage actor. Inside the shop, the spell breaks. Racks of Donald Trump t-shirts, plastic toys, luggage, snow globes. The ordinary commerce of a tourist corridor. The wizard is only skin.

And yet, that skin matters. The wizard’s absurdity is his power. He is both parody and survival strategy. A knock-off magician conjured to compete with a kingdom of billion-dollar fantasy. He doesn’t fool anyone, but he doesn’t have to. He exists to be seen.

There’s a kind of dignity in that. The wizard is ridiculous, but he’s also stubborn. He keeps his staff raised, night after night, over an economy that chews up small shops and spits them out. He says, in his silent fiberglass way: we are still here.

Fireworks Over the Corridor

Stand in the Wizard Gift Shop parking lot on a summer night and you’ll see something surreal. To the west, over the treeline, fireworks bloom from Disney’s Magic Kingdom. They explode in bursts of color, choreographed to music that only paying guests can hear. But the light travels. Families lean against cars in the lot and watch the sky. The fireworks were not meant for them, but they get them anyway.

This is the paradox of Highway 192. On one side of the line is Disney’s curated perfection. On the other is a corridor of motels, diners, neon signs, and fiberglass fruit. The glow of one spills into the other. Fantasy leaks across property lines.

It would be easy to laugh at the knock-offs, the giant orange and the wizard. But there’s something sharper at play. These facades are not simply failed copies. They are working-class adaptations. They are survival tactics in the shadow of a company that perfected the art of selling dreams.

Behind the neon, though, reality pushes through. The same motels that once housed vacationers now hold families permanently. For many, the weekly rates of a roadside motel are the only option left. The lights of Cinderella’s castle flash across the same sky as the flicker of eviction notices.

The Florida Project and the Magic Castle Motel

The Magic Castle Motel used to be impossible to miss. It was painted a violent purple, with fake turrets jutting from the roofline. It looked like a child’s drawing of a castle, cheap and playful, designed to catch families headed for Disney. That coat of purple made it famous, especially after Sean Baker used it as the setting for his 2017 film The Florida Project.

But the castle has been repainted. The new owners covered the purple in a flat white.

The paint makes it look like any other roadside motel. Drab, blank, anonymous. What was once a landmark has been stripped of its identity. It feels like a deliberate scrubbing, a way to distance the property from its reputation as both a cultural icon and a symbol of poverty.

For the families who live there, the paint doesn’t change the rent, the instability, or the reality of motel poverty. But for the passerby, the magic is gone. The building is less visible now, less memorable, harder to distinguish from the hundreds of other motels along the corridor.

It is a small act of erasure, but one that fits the larger story. The strip has always been about facades, and now even one of its most famous facades has been flattened into something neutral. The purple castle of the film exists only on screen, preserved in celluloid, even as the real walls have been painted over.

The statistics remain the same. More than 5,000 children in Osceola County are considered homeless under federal guidelines. Many live in motels on this corridor. Their parents often work in the very industry that props up Disney. Cleaning rooms. Serving food. Driving shuttles. The wages do not cover rent, so the motel becomes the default.

The irony cuts deep. Families spend more per month on a motel room than they would on an apartment, but without the deposits or background checks, there is no other way in. Stability is out of reach. The fireworks burst overhead each night, paid for by the same machine that keeps wages low, and the kids in the motels watch from the parking lot.

Between Fantasy and Survival

Orange World and the Wizard Gift Shop are absurd structures, but they are also honest. They make no attempt to disguise their purpose. They want to be seen. They want you to pull off the road. They want you to believe, if only for a moment, that a giant fruit or fiberglass wizard has something to offer.

They stand as both parody and protest. Parody of Disney’s fantasy economy. Protest against being erased by it. These buildings are stubborn. They hold their place along the strip, year after year, even as the groves vanish, even as the motels fill with families, even as the shadow of the Magic Kingdom grows longer.

For the children who grow up here, the facades become landmarks. The purple motel becomes a castle. The wizard becomes a guardian. The giant orange becomes a compass point. The architecture may be kitsch, but the memories are real.

Driving away, I think about what these buildings say about America. They are oversized, hopeful, desperate, and enduring. They are not Disney’s castles, but they are not lies either. They are survival made visible.

At night the wizard’s neon staff glows. Orange World’s rind catches the shimmer of fireworks. Together they mark the line where fantasy and reality meet, where spectacle and poverty share the same sky. They are strange monuments, but they are ours.