"Drowned in Glory" The Colonial Epitaph That Refused to Lie

How a young physician's drowning became Hartford, Connecticut's most unflinching memorial

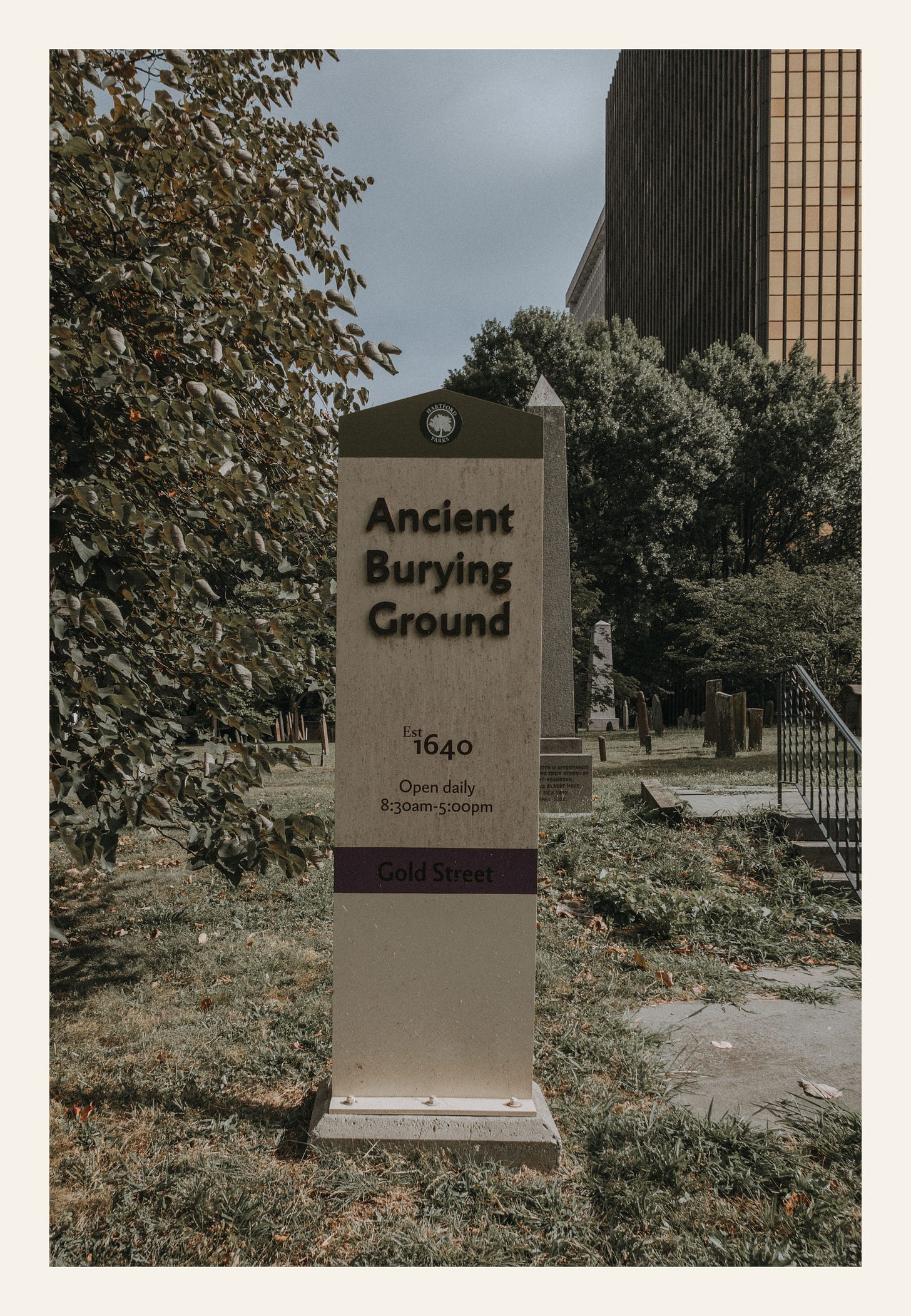

Most colonial epitaphs read like résumés for the afterlife: beloved father, devoted wife, faithful servant of God. They're carved propaganda, designed to scrub away the messy realities of how people actually lived and died. But walk through Hartford's Ancient Burying Ground and you'll find one gravestone that breaks the mold entirely.

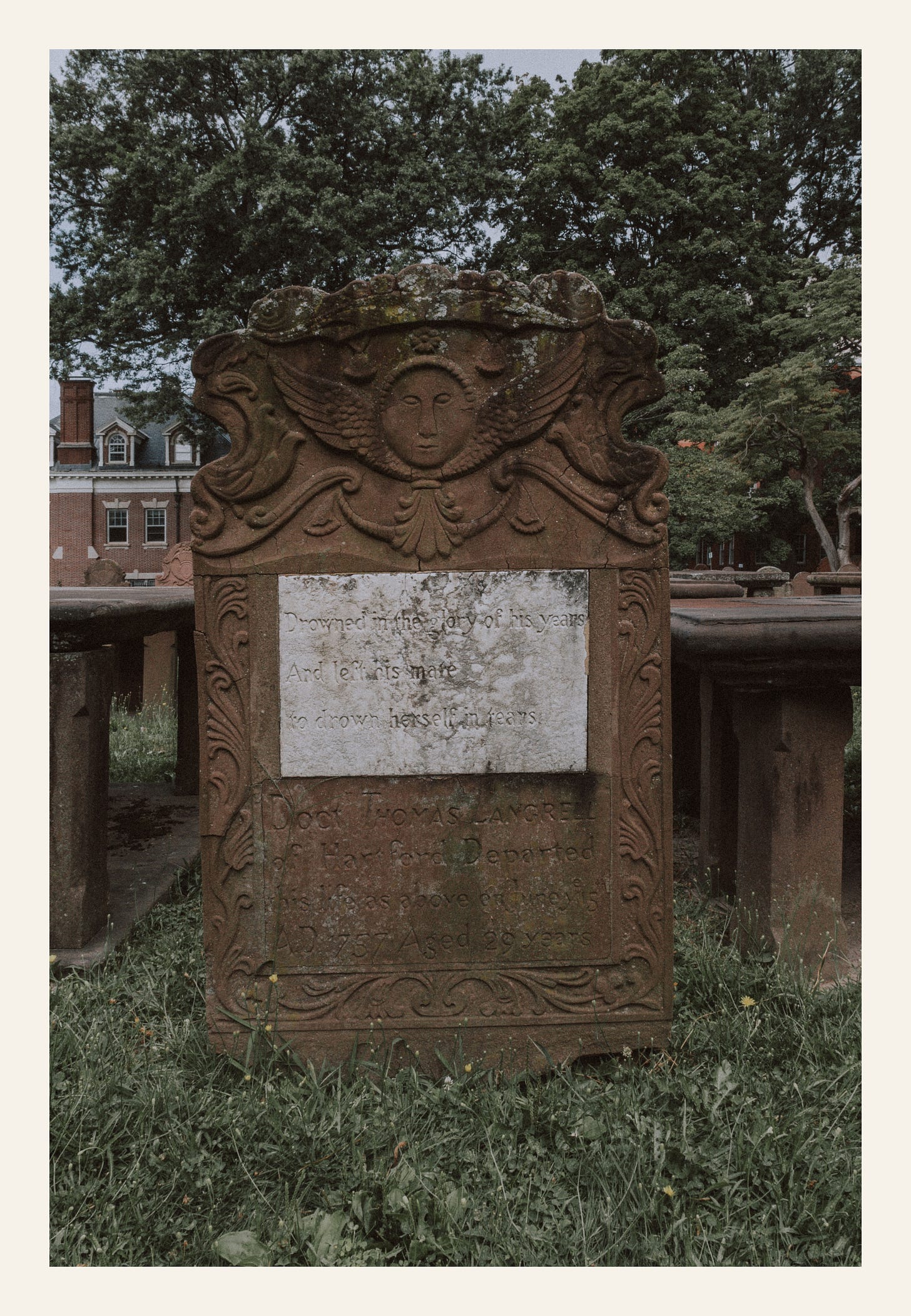

"Drowned in the glory of his years and left his mate to drown herself in tears."

The words hit like a punch to the chest. This isn't pious platitude or gentle euphemism. This is raw grief carved in stone, and it belongs to Dr. Thomas Langrell, who died at 29 in 1757 trying to save a drowning stranger. His story, buried for centuries in crumbling church records and yellowed newspaper archives, reveals how quickly heroism could turn fatal in colonial America.

Finding Langrell required detective work. Hartford's Center Church sexton records provided the first clue: a single line recording the burial of "Dr. Thomas Langrell 2d" on June 16, 1757. No cause of death, no family details, just a name and a date. The "2d" suggested he was a junior, meaning there had been another Thomas Langrell before him.

Harvard College's archives filled in the next piece. Langrell graduated in 1751, one of roughly 20 men in his class. Most Harvard graduates of that era entered the ministry. Langrell chose medicine, establishing himself as an apothecary in Hartford by his mid-twenties.

Colonial apothecaries occupied dangerous territory between university training and folk remedies. They diagnosed ailments, set bones, and mixed medicines in an era when medical knowledge could kill as easily as cure. For a 25-year-old with a Harvard degree, it represented both opportunity and constant risk.

Marriage records from 1754 showed Langrell wed Mary Hyde of Norwich, connecting him to one of Connecticut's most prominent families. The strategic alliance made sense: Mary's father, Captain William Hyde, commanded respect throughout the colony. More significantly, Langrell's sister Abigail had married Mary's brother, creating the intertwined family networks that defined colonial society's upper reaches.

The couple never had children, a fact later recorded in genealogical documents with the Latin notation "s.p." (sine prole, without issue). Mary would outlive her husband by nearly a decade, dying in 1766 at what was still considered a relatively young age.

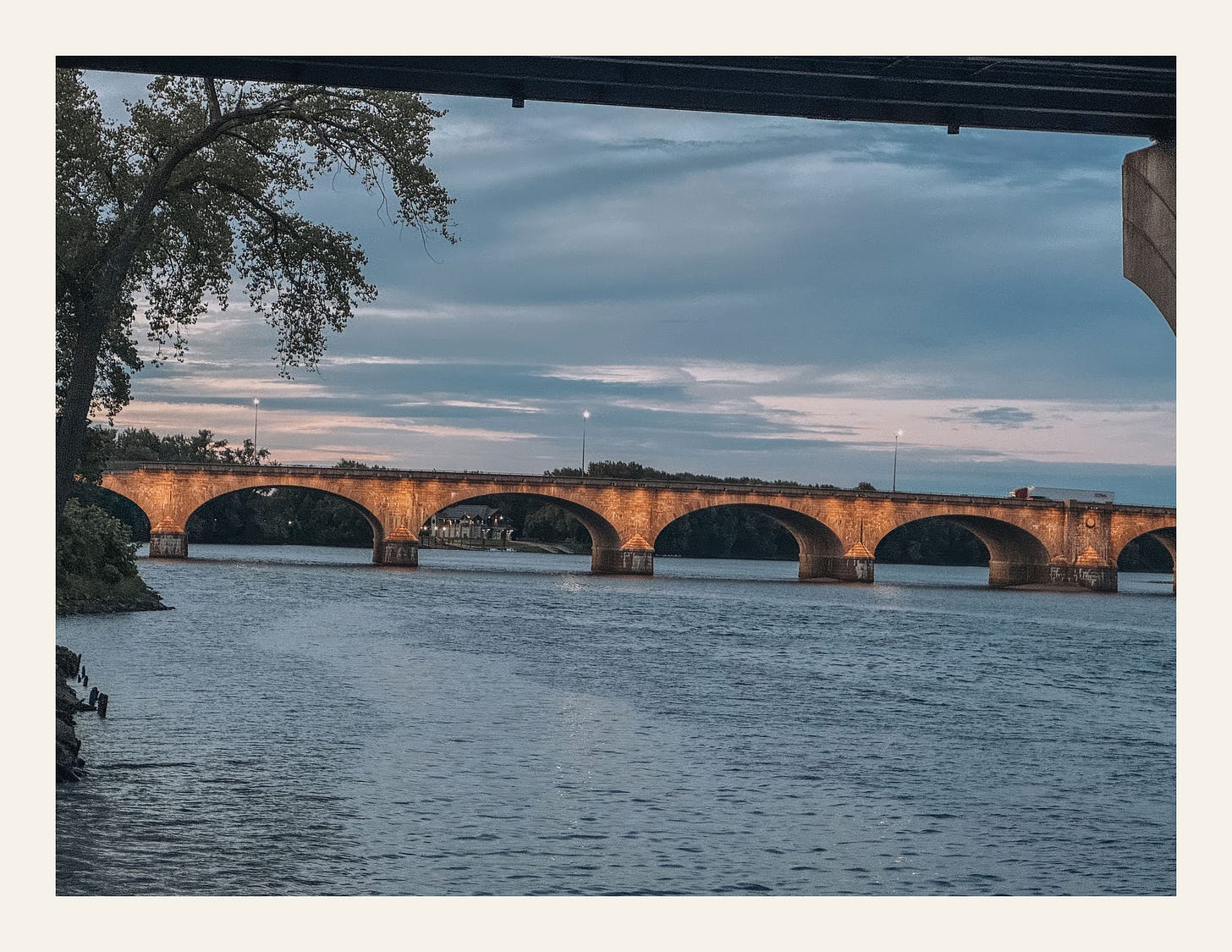

Hartford in the 1750s balanced commercial promise with daily peril. The Connecticut River served as the town's economic lifeline while posing constant danger. No permanent bridge would span the water until 1808, leaving residents dependent on small ferry boats that navigated unpredictable currents and seasonal flooding.

River crossings were routine necessities that occasionally turned deadly. The French and Indian War, raging from 1754 to 1763, added another layer of uncertainty. While Hartford avoided direct military action, the conflict drained resources and sent local men to fight in distant campaigns.

Against this backdrop, Langrell built his practice. His shop likely occupied ground-floor space along one of Hartford's main streets, with living quarters above and a workshop where he prepared medicines according to Harvard formulas while adapting to local conditions.

An unexpected detail about his household emerged from an 1837 pension deposition, discovered in Revolutionary War veteran records. A widow seeking benefits testified that her late husband "had some years before been a slave of Doct. Langrel of Hartford who was a physician and kept an apothecary store," where he learned to "prepare and mix medicines." The account revealed how medical knowledge circulated through unexpected channels while showing how slavery remained woven into Connecticut's daily life.

The circumstances of Langrell's death finally surfaced in the Connecticut Gazette of June 18, 1757. The newspaper's account, typical of colonial reporting in its brevity, described a collision between two ferry boats on the Connecticut River. A ferryman fell into the water. Langrell and another passenger, William Harpy of Harvard, Massachusetts, jumped in to attempt a rescue.

All three drowned.

The sexton's burial records confirmed that both Langrell and Harpy were interred side by side on June 16, 1757. The timing suggested their bodies were recovered within a day or two, probably caught by river bends or shallow areas downstream from Hartford.

River drownings were common enough that newspapers rarely devoted much space to them unless the victims were particularly prominent. What distinguished Langrell's case was not how he died but the extraordinary poetry carved into his gravestone afterward.

"Drowned in the glory of his years" captured both the tragedy of a life cut short and the heroic nature of his final act. The phrase suggested someone in his prime, professionally established and personally fulfilled. The second line gave voice to Mary's grief while employing drowning as a metaphor, connecting her emotional devastation to her husband's physical fate.

The epitaph's author remains unknown, though it likely came from Mary herself or a family member with literary inclinations. Colonial gravestone poetry often combined classical references with personal sentiment, creating verses that functioned as both memorial and moral instruction.

But who could afford such elaborate stonework? And why did this particular death warrant poetic treatment when hundreds of other drowning victims received simple markers?

The answer lies in education, family connections, and timing. Langrell represented the emerging professional class in colonial America: Harvard-educated, well-married, positioned to benefit from the colony's growing prosperity. His death came not from disease or old age but from attempted heroism, the kind of sacrifice that colonial society particularly valued.

The gravestone reflects changing attitudes toward death and memory in 18th-century New England. Earlier Puritan markers emphasized mortality's universality with carved skulls and biblical verses. By the 1750s, epitaphs had become more personal, celebrating individual character while still acknowledging divine providence.

Langrell's story illuminates the precariousness that defined colonial life even for the educated and well-connected. Harvard degrees and prominent marriages provided advantages, but they offered no protection against river currents or ferry accidents. Disease, weather, and bad luck could undo years of careful planning in moments.

His tale also reveals how quickly heroic acts could turn tragic when rescue techniques were primitive and safety equipment nonexistent. The decision to jump into turbulent water reflected values that colonial sermons regularly promoted, but it could prove fatal when applied to genuinely dangerous situations.

Mary Langrell's widowhood, lasting nearly a decade after her husband's death, suggests something about the limited options available to women in her position. Colonial records provide few details about how she spent those years, whether she remained in Hartford or returned to family in Norwich, whether she considered remarrying or chose to preserve her connection to her late husband's memory.

Her relatively early death in 1766 raises questions about grief's long-term effects and the health challenges facing colonial women. Medical knowledge of the era offered little understanding of psychological trauma, leaving widows to cope with loss using resources provided by family, church, and community.

The epitaph's enduring presence in downtown Hartford creates an accidental monument to the city's colonial past. In a place that has largely erased its early history in favor of insurance company headquarters and urban renewal projects, Dr. Thomas Langrell's gravestone stands as one of the few remaining testaments to the people who built Hartford from wilderness into a thriving river port.

His final act speaks to values that transcend historical periods: the willingness to risk everything for a stranger's life, even when success seems impossible. The words that memorialize his drowning have outlasted most of the institutions and families that once defined Hartford's colonial society.

They remain, carved in stone, waiting for the next passerby to stop and wonder about the young doctor who drowned in the glory of his years. Sometimes the most honest epitaphs are the ones that refuse to lie.

Were you visiting Hartford? Next time give a shout & we can meet up!