The Mourning Doves of Lovejoy Cemetery

The circus wreck, the unknown dead, and the evening doves of Durand, Michigan

This is why I always visit cemeteries everywhere I go. There's usually a story. And even when it's a gut wrenching sad story, it's an interesting story worth telling. The 1903 circus train wreck in Durand, Michigan, left behind one of the most haunting memorials I've ever encountered.

The Lovejoy Cemetery in Durand, Michigan, is easily one of the most beautiful I've been to. It was evening when I visited, and perfectly quiet minus the wind and two dueling mourning doves. Their hollow calls echoing across the headstones like some ancient conversation about loss and memory. The cemetery is old. A lot of the plots are in disrepair, but still beautiful in that way that only forgotten places can be, where time has softened the hard edges of grief into something almost peaceful.

From the cemetery's edge, you can see gorgeous farmland rolling away toward the horizon. Neat rows of soybeans and corn stretching into the distance like green waves frozen mid-motion. It's the kind of view that makes you understand why people settle somewhere and decide to stay forever, even after forever comes calling.

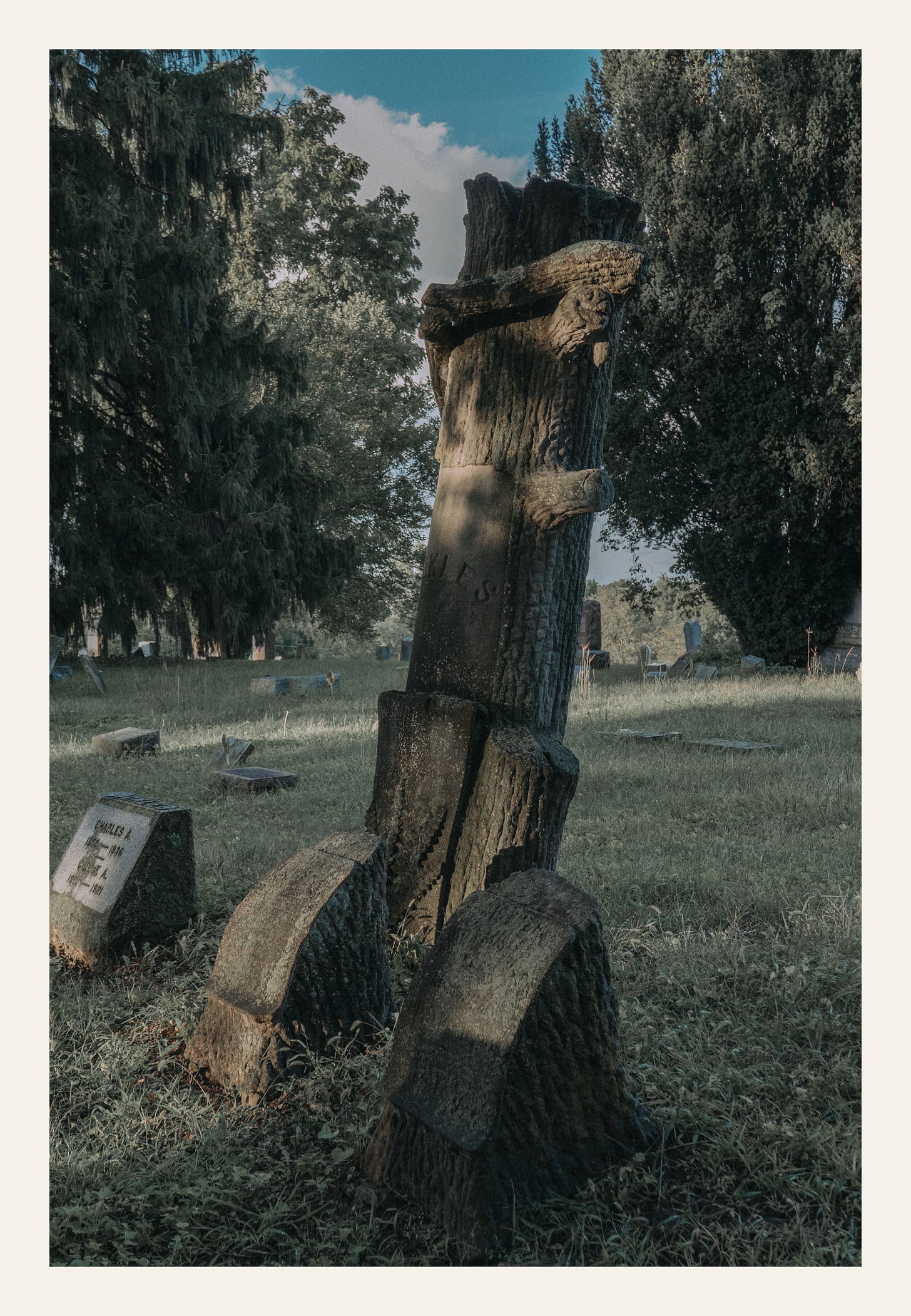

But it's the giant tree that draws you in. Some massive weeping specimen with branches that cascade down like a natural cathedral, seemingly protecting an inner section of plots where many of the headstones bear dates that break your heart. Children, mostly. The smaller stones tell their own quiet stories: "Our Baby," "Gone Too Soon," names and dates that span mere months or single-digit years.

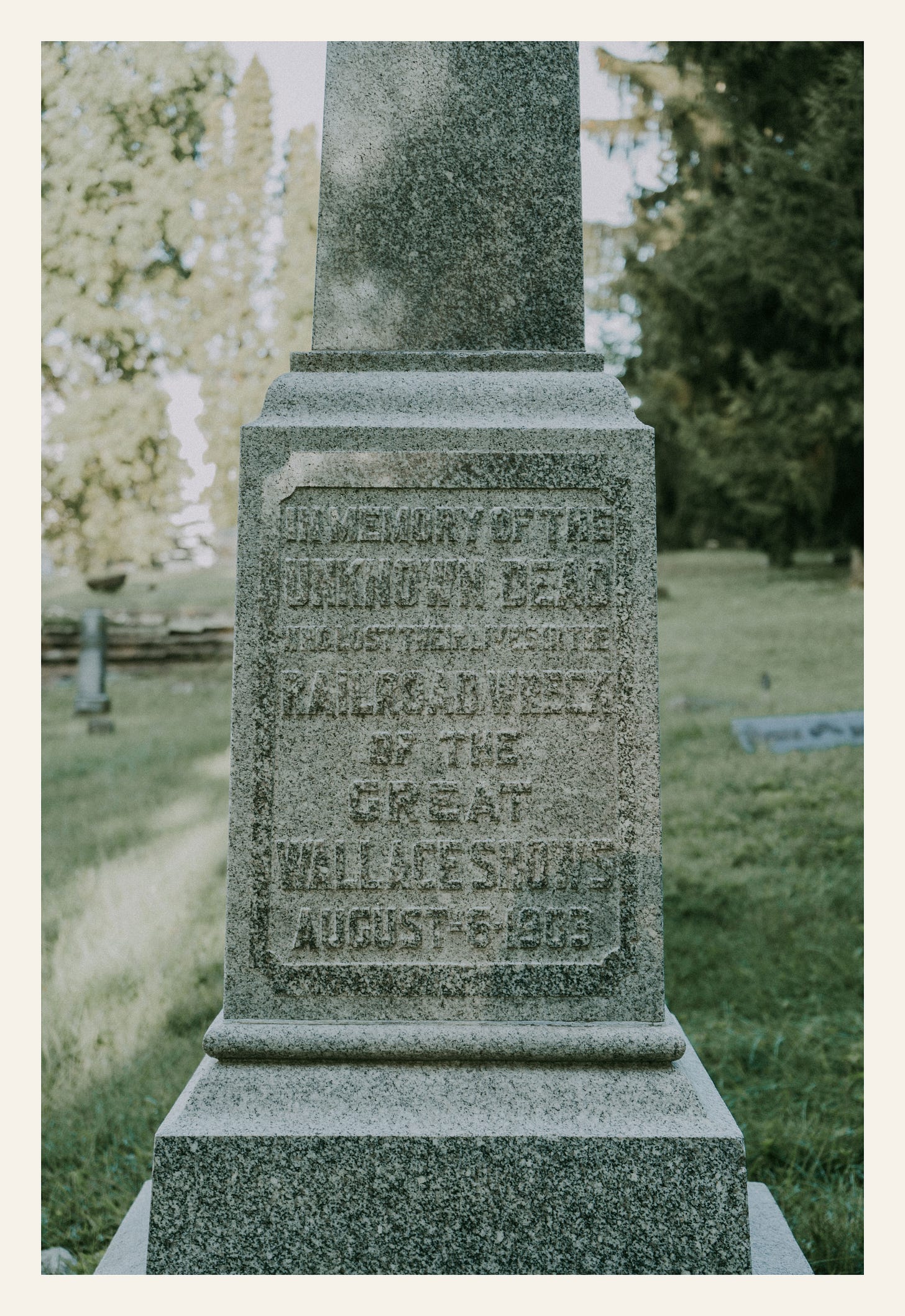

And then there's the obelisk.

It rises from the earth near the cemetery's entrance like an accusing finger pointed at the sky, gray granite weathered but still legible: "In Memory of the Unknown Dead... Railroad Wreck of the Great Wallace Shows – August 6th, 1903." Ten people buried together, their names lost to history, but their story somehow more powerful for its incompleteness.

Durand has always been a train town. You can feel it in the bones of the place. The way the streets orient themselves toward the tracks, the way the old depot still squats near downtown like a patient dog waiting for its master to return. The Grand Trunk Railway made Durand into something more than just another Michigan farming community. It became a hub, a place where rails converged and diverged, where freight trains and passenger cars paused to take on water and coal before continuing their journeys across the vast American grid.

The depot, built in 1903 (the same year as the wreck) was a marvel of brick and limestone, with its tall windows and clock tower presiding over the controlled chaos of America in motion. Passengers would spill out onto the platform, stretch their legs, buy newspapers and sandwiches from vendors who worked the crowd with practiced efficiency. The air would smell of coal smoke and coffee, hot metal and possibility.

But the real action happened in the yards. That sprawling network of switches and sidings where trains were assembled and disassembled like some enormous mechanical puzzle. This is where circus trains came to rest, where the Wallace Brothers' Great Show would pause between performances, their cargo cars full of canvas and costumes, their stock cars carrying the menagerie that would soon delight crowds in the next town down the line.

On the night of August 6, 1903, two sections of the Wallace circus train sat in those yards. The first section (heavy with equipment cars and a caboose full of workers) had stopped on the main line, a red lantern glowing behind it like a warning that wasn't quite warning enough.

Picture it: 3:45 AM in the rail yard. The kind of hour when the world feels suspended between night and morning, when even the most familiar places take on an otherworldly quality. The first section of the circus train sits quiet on the tracks, its cargo cars loaded with the carefully folded dreams that will soon become a three-ring spectacle under canvas. In the caboose, men sleep the hard sleep of manual labor. Drivers and riggers, the invisible army that makes magic possible.

Thirty minutes behind schedule, the second section rounds the curve at fifteen miles per hour. Not fast by train standards, but fast enough. Inside the sleeping cars, the circus owners and performers rest easy, trusting in steel and steam and the simple physics of stopping.

Except the air brakes fail.

It's such a small thing, really. A mechanical failure, a system that had worked a thousand times before choosing this moment, this curve, this sleeping caboose full of working men to finally give up. The locomotive plows into the rear of the first section with the inevitability of a Greek tragedy, metal meeting metal with a sound that wakes half of Durand and haunts the other half.

Twenty-three people die. Maybe twenty-six, depending on how you count those who linger for days before succumbing. The circus performers in the second section (protected by luck and sleeping car construction) emerge mostly unscathed. But the men in the caboose, the anonymous laborers whose names were never printed in the circus programs, become headlines for all the wrong reasons.

And it's not just the humans. Maud the elephant (or Maude, the spelling varies with the source) dies along with camels and horses and dogs, the show's menagerie reduced to casualties buried in unmarked graves beside the tracks. The papers make much of the elephant, because an elephant's death feels biblical in its tragedy, but the horses and camels and faithful hounds are noted almost as afterthoughts, their smaller lives somehow expected to matter less.

The aftermath moves with the efficiency of a small town that's been forced to confront something larger than itself. The Richelieu Hotel becomes a makeshift hospital. Doctors arrive on special trains. Undertakers work through the heat of August, their grim business made more complicated by the task of identifying bodies when half the dead are drifters and seasonal workers whose next of kin might be anywhere or nowhere.

Ten of the victims are never identified. Ten working men whose names disappear into the same anonymity that claimed their lives, buried side by side in Lovejoy Cemetery under a stone that tells their story in the starkest possible terms, according to the Shiawassee County Historical Society. They become the Unknown Dead, which is both more and less than they were in life.

The circus, of course, goes on. It always does. The Wallace Brothers salvage what they can, bury what they can't, and within days the show is moving again, trailing its peculiar mixture of wonder and exploitation toward the next town, the next audience, the next careful setup in another rail yard where the brakes will hopefully work as designed.

But Durand remembers. The depot still stands. The rail yard still hums with freight trains, though circuses travel by truck now when they travel at all. And in Lovejoy Cemetery, that obelisk still points skyward, marking the spot where ten anonymous lives intersected with mechanical failure and small-town decency in a way that created something approaching immortality.

The mourning doves are still calling when I leave, their voices carrying across the farmland that stretches beyond the cemetery's edge. In the gathering dusk, the weeping tree looks like a guardian angel with trailing wings, protecting its charges from a world that can be cruel in the most random ways.

This is why I visit cemeteries. Not for the morbid fascination, but for the stories—the way individual tragedies become collective memory, the way a small town's response to disaster can teach you something about human decency that you didn't know you needed to learn.

The Unknown Dead of the Wallace Brothers circus wreck have been sleeping here for more than a century now, their names lost but their story preserved in granite and in the collective memory of a town that refused to let them disappear completely. It's not much, maybe, but it's something. In a world that tends to forget the anonymous and the disposable, it's something.

And sometimes, when the mourning doves call across the evening fields, something is enough. Atlas Obscura's guide to the Great Wallace Shows memorial notes that visitors still come to pay their respects, drawn by the same impulse that brings me to cemeteries everywhere I go: the need to witness, to remember, to acknowledge that these lives mattered.

The historical disaster records show that this was one of dozens of circus train wrecks that occurred during the golden age of traveling shows, when railroads crisscrossed America carrying dreams and nightmares in equal measure. But in this quiet cemetery, under the protective branches of an ancient tree, the statistics become human again. Twenty-three lives. Ten unknown names. One elephant named Maud. All of them worth remembering.